Experimenting on the Farm: A Necessity in 18th Century America and Beyond

Experimental farming was an epic part of early American history.

From James Madison's Merino sheep to George Washington's tests with manure, experimental farming was necessary if the goal was creating a nation from a former colony.

I'll tell you why (as I've learned and processed it) but know that there's a super-good chance this post will be updated. For now, I wanted to get my thoughts down while they were fresh in my mind but there's more research I want to do- because I LOVE this topic. I will continue to visit what I call Farmer Ed's "lab" (aka Ewing Farm here in Colonial Williamsburg) because he pretty much provides the best education.

RELATED: This article by Ed Schultz, my go-to for 18th century (and beyond) agricultural information.

UPDATE March 2024: An interview with Ed is available here.

Necessary disclaimer: As a blogger, I use affiliate links sometimes! I may receive commission from purchases I share; it does not change your price but sometimes you might get a discount.

Interpreter farming tobacco at Jamestown Settlement, Virginia

Why was it necessary to experiment on farms in the 18th century?

Evolving from a colony to a country meant we had to build an economy, truly from scratch as I'm seeing it. Col. Washington gave us quite an education yesterday at Ewing Field here in Colonial Williamsburg (CW) - a place I already mentioned that I lovingly call "Farmer Ed's lab."

Basically Daniel Cross, in character as Washington, took all the bits and bobs of agriculture I've been learning, and explained/re-explained it in a way that flipped a switch in my head.

Yes, I've known from conversations throughout the trades shops to hearing presentations by our actor historians here in Colonial Williamsburg (CW), and probably even from some history education "back in the day," that as a colony, we were reliant on England.

Simply put, here's the visual from the Colonel: colonies are meant to support the mother country by sending her the raw materials and resources mama doesn't have and buying back finished products from the industrialized parent.

Perhaps it sounds a bit over-simplified, but for purposes of this blog, not only is it accurate, but it's enough to start the conversation (you can always dig deeper my friends- I will!).

From tobacco to the rest because: independence and soil preservation!

Tobacco was king... for a LONG time.

From the settlement at Jamestown well into the 18th century, early American farming, and our economy, was based on tobacco.

RELATED: Love and Hate in Jamestown references the history of settling in North America and the shift into tobacco farming.

However, I'm continuously told it wasn't a cash crop in the sense Americans actually wandered around with actual cash. In fact, it was all about credit. We were selling tobacco back to England and of course, that was the only place we really could sell it, by law.

Tobacco was problematic beyond the fact that the credit tobacco farmers would be able to transfer over into purchases was pretty much speculative. This is the crux of it: tobacco depletes the soil. Insanely.

Farmers like Washington saw the need for soil preservation as well as diversification.

And, ultimately, with our independence, we as a nation needed to diversify and not only source the raw materials, but process and manufacture them into actual products. As the 19th century hit, as our nation expanded, and as our need for a self-sustaining economy became critical, the northern cities became industrialized.

That's a post for another day! In the meantime, if American industrialization is something you have a passion for and possibly an education on, feel free to hit me up- I'd love to chat!

Tobacco at Ewing Field in CW, August 2023

So let's talk about this soil issue.

One reason Col. Washington tells us he strays from tobacco is the depletion of the soil. You can only grow quality tobacco for a few short years, then rotate in a lesser crop (my words, not his) but eventually have to let the ground go fallow for something like 15-20 years.

Yes, you heard that right; that was crazy long to someone like me with no agricultural background. Clearly, it was necessary to figure out what you can grow in the ground repeatedly without having to literally buy up more land in order to continue farming.

Washington experimented with how to preserve the soil and do what we call "sustainable" farming today. Using red clover and manure are two examples, but there are more.

Excerpt from Washington's 1787 letter to Charles Carter (click here to read in full with citations). The topic: experimenting with manure strategies!

In level ground, as equal in quality as I could obtain it, I laid of 10 squares; each square containing by exact measurement, half an acre. half of each of these I manured at the rate of 200 bushls of well rolled farm yard dung to the Acre to ascertain the difference between slight manuring such as we might have it in our power to give the land, and no manure.

CW's Col. Washington explaining the history of tobacco farming in Virginia at Ewing Field.

Then there was the political statement these gentlemen wanted to make.

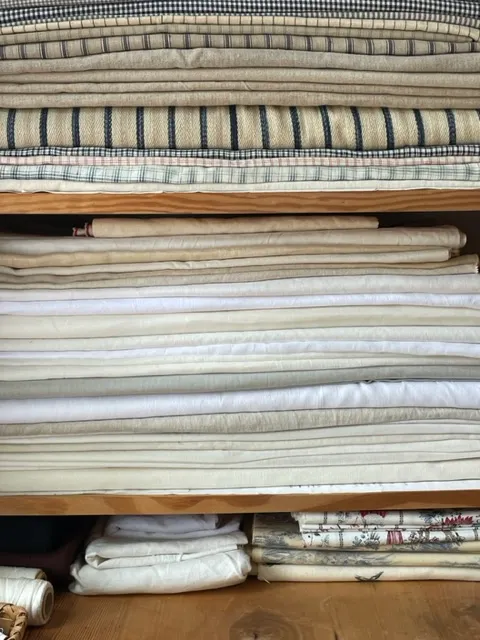

Whenever we visit the dye and weave shop, it's made clear how expensive (and labor-intensive and simply ridiculous) it would be for Americans in the 18th century to be spinning wool, dyeing it and weaving textiles to make clothing for themselves on a regular basis, let alone to sell and create an industry from it.

One reason: we didn't have the sheep. Washington managed to get a couple Bakewell rams which were developed to provide long hair for wool. Most sheep in the Colonies (American) were meant for meat, not wool.

By Washington, Jefferson, and others having looms on their properties, it was a blatant statement against having to purchase textiles from England. The reality: it was a statement, hardly possible to truly create an industry to compete with England's textile manufacturing.

Summer linens in the CW tailor shop, examples of imported textiles.

It wasn't just Washington, other early American farmers and landowners experimented.

Washington wasn't the only one doing this... but typically I'm guessing you'd find farmers with wealth experimenting. They could afford to. If it took Washington 8 years (and it did!) to move away from tobacco completely, it follows that a farmer with limited land would be less likely to mess around with their crops.

So who did experiment?

At the opening of this post I mentioned James Madison and his merino wool. I wrote about that a bit in this post on sheep.

Jefferson was really into agriculture as you might already know. From experimenting with grapes for wine to figs from French seeds (as mentioned in his letter to George Wythe in October 1794), he was 100% fascinated by nature, and in turn, experimental farming.

Our Jefferson in CW often wanders around with a magnolia leaf- a tool to discuss botany with younger visitors.

Landon Carter was one of the wealthiest men in Virginia and kept a diary about everything basically! But for purposes of this article, his detailed notes on farming are vital primary resources and he corresponded with the names more familiar to most of us.

It seems early Americans were constantly testing out what will work from one region to the next.

Writing about plants, food, and anything agriculture can be found pretty easily in primary sources like this excerpt from a 1758 letter from Benjamin Franklin.

"I hope the Crab Apple Trees you have planted will grow, and be propagated in our Country. I do not find that England any where produces Cyder of equal Goodness with what I drank frequently in Virginia made from those Crabs. They are also said to be plentiful Bearers, and seldom fail. I should be glad to see the Industry of our People supplying the Neighbouring Colonies with that Cyder. I think it would even be valued here."

And don't forget that Nathaniel Greene's widow, Caty Greene Miller, inspired her employee Eli Whitney's innovation that changed history: the cotton gin.

Tobacco and cotton collected at CW's Ewing field.

Want to learn more about agriculture in early America?

Here are my recommended reads:

This article specific to Washington on Mt. Vernon's website and this article about pumpkins on CW's site, which mentions Washington's growing them!

If you're ready to dive deep, get into the Carter archives, starting here!

Founding Gardeners, by Andrea Wulf and as of August, 2024, my discovery of Thomas Jefferson's Garden Book. You can read my post about it here.

Closing it out with a letter from Washington to Mr. Carter about his testing out carrots and potatoes. For the citations, click here.

From George Washington to Landon Carter, 11 September 1799

To Landon Carter

Mount Vernon 11th Sep: 1799

Dear Sir,

In answer to your favor of the 6th instant, which I received yesterday;1 I inform you that I have raised no Carrots in the field these ten or twelve years; of course, have no other seed than such as are usually cultivated in Gardens.

Previous to the year 1789, when I was drawn from retirement; I cultivated both Carrots & Potatoes (in alternate rows) between drilled Corn 8 feet a part,2 and am persuaded that the aggregate benefit from the practice would be found highly profitable to a Farmer who has it in his power to attend to his business himself, and will be judicious in the application of them. Without this, they turn to little account in the hands of such Overseers as are employed in common. I did not find that they yielded equal to the Potatoes, but were more nutritious as a food for Milch Cows. With esteem I am—Dear Sir Your Obedt Hble Servt

Go: Washington

Enjoying this blog? I have an online tip jar! Click here to tip me.

There is a huge practical disclaimer to the content on this blog, which is my way of sharing my excitement and basically journaling online.

1) I am not a historian nor an expert. I will let you know I’m relaying the information as I understand and interpret it. The employees of Colonial Williamsburg base their presentations, work, and responses on historical documents and mainly primary sources.

2) I will update for accuracy as history is constant learning. If you have a question about accuracy, please ask me! I will get the answer from the best source I can find.

3) Photo credit to me, Daphne Reznik, for all photos in this post, unless otherwise credited! All photos are personal photos taken in public access locations or with specific permission.